Epidermolysis Bullosa, or EB, is a group of rare disorders caused by a mutation in one of 18 genes. There are four major types: Simplex, Junctional, Dystrophic, and Kindler, and the specific type of EB is determined by the affected gene.

EB affects 1 out of every 20,000 births in the United States (approximately 200 children a year are born with EB). People with EB share the lifelong challenge of extremely fragile skin that blisters and tears from minor friction or trauma. The list of medical complications EB causes may be long and often requires multiple interventions from a range of medical specialists. EB affects all genders and racial and ethnic groups equally.

There is no cure for EB but there are treatments that help alleviate some of the debilitating symptoms of certain types of EB. The current standard of care for EB is supportive, which includes daily wound care, pain management, and protective bandaging. Learn about debra of America’s wide range of programs and services that help ease the many burdens of EB.

On this page, you will find information on the major types of EB and their associated subtypes. There are 4 major types, each caused by a different genetic mutation:

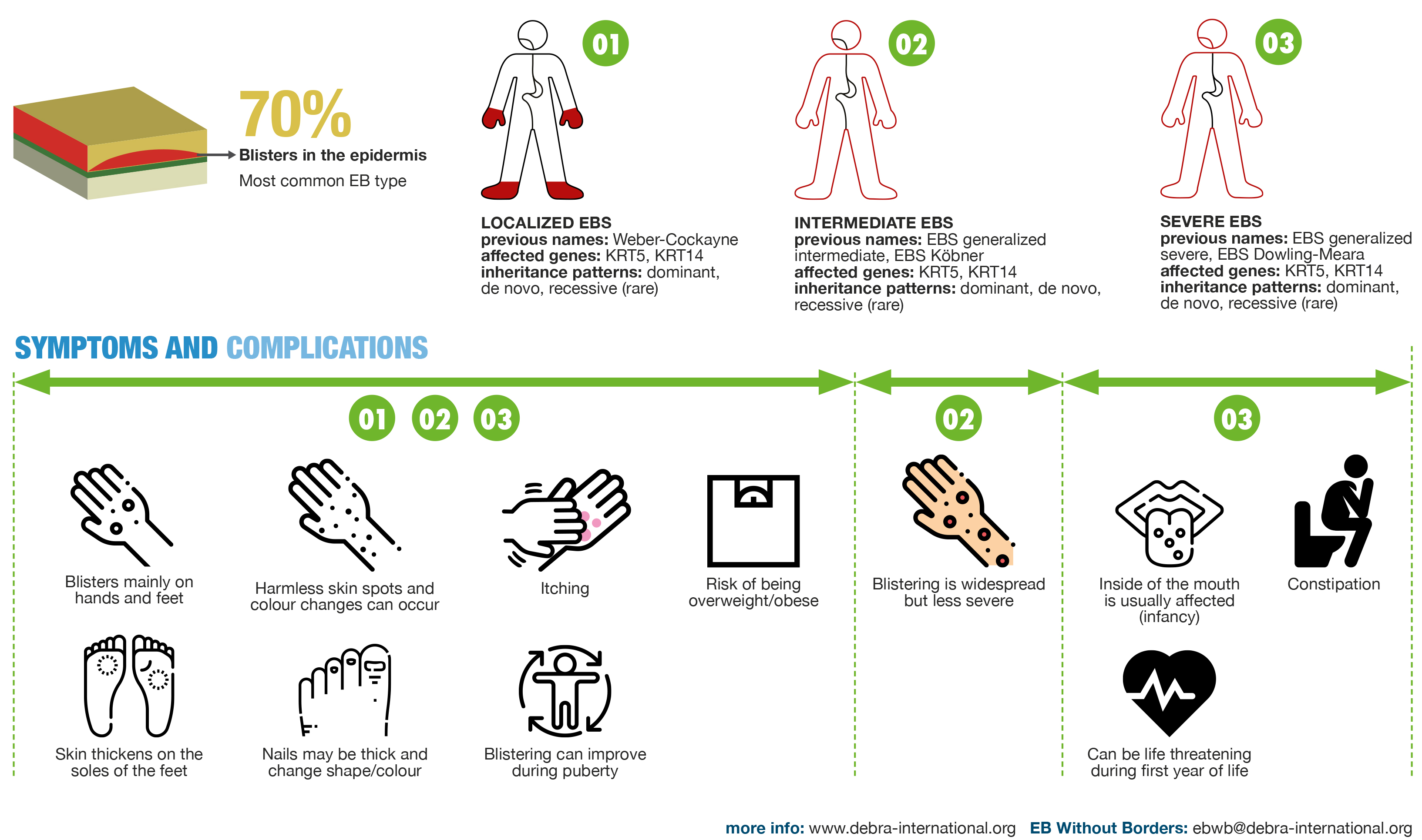

Simplex

EB Simplex is the most common type of EB, with most mild cases remaining underdiagnosed. EBS is defined by skin blistering due to cleavage within the basal layer of keratinocytes.

In most cases, EBS is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner; autosomal recessive inheritance is rare in Western countries but quite common in some regions in the world. There is a broad spectrum of clinical severity ranging from minor blistering on the feet, to subtypes with extracutaneous involvement and a lethal outcome.

Common EBS subtypes include Localized, Intermediate, and Severe EBS.

Localized EBS

Previously known as Weber-Cockayne

Noted Clinical Symptoms

- Skin blistering begins at birth or in early infancy. The intra-epidermal blistering is superficial, leading to erosions and crusts, and is enhanced by heat, humidity and sweating. The tendency to blistering diminishes in adolescence, when it may become localized to hands and feet. Blisters may heal with hyperpigmentation.

- Milia may occur in the first weeks of life.

- Plantar keratoderma occurs and develops gradually, is painful, may reduce mobility, and may strongly impair quality of life.

- EB naevi are common.

- Nails may be thick and dystrophic.

Intermediate EBS

Previously known as EBS generalized-severe, EBS Köbner

Noted Clinical Symptoms

- Skin blistering begins at birth. The intra-epidermal blistering is superficial, leading to erosions and crusts, and is enhanced by heat, humidity and sweating. The tendency to blistering diminishes in adolescence, when it may become localized to hands and feet. Blisters may heal with hyperpigmentation.

- Blistering is generalized, but less severe compared to Severe EBS.

- Milia may occur in the first weeks of life.

- Plantar keratoderma occurs and develops gradually, is painful, may reduce mobility, and may strongly impair quality of life.

- EB naevi are common.

- Nails may be thick and dystrophic.

Severe EBS

Previously known as EBS generalized severe, EBS Dowling-Meara

Noted Clinical Symptoms

- Skin blistering begins at birth. The intra-epidermal blistering is superficial, leading to erosions and crusts, and is enhanced by heat, humidity and sweating. The tendency to blistering diminishes in adolescence, when it may become localized to hands and feet. Blisters may heal with hyperpigmentation.

- Milia may occur in the first weeks of life.

- The oral mucosa is usually involved in infants.

- Skin fragility is very prominent at birth, and congenital ulcerated areas on hands and feet as well as nail involvement are common. In the neonatal period, large tense blisters can occur after minimal mechanical trauma or spontaneously. The condition may be life threatening in the first year of life.

- Plantar keratoderma occurs and develops gradually, is painful, may reduce mobility, and may strongly impair quality of life. Confluent palmoplantar keratoderma is mostly seen in severe EBS.

- EB naevi are common.

- Nails may be thick and dystrophic.

- Gastro-oesophageal reflux may occur in infancy, often needing aggressive medical treatment.

- Growth retardation is common in infants.

Noted Clinical Symptoms

-

Skin blistering starts at birth and is generalized, of intermediate severity.

-

Mottled or reticulate pigmentation develops gradually

-

Focal keratoses of the palms and soles, and dystrophic, thickened nails occur over time.

Genetics

-

Autosomal dominant inheritance.

-

The keratin 5 monoallelic pathogenic variant c.74C>T, p.P25L typically causes this phenotype,13 but cases with other variants in KRT5, KRT14 or EXPH5 have been reported.

Noted Clinical Symptoms

-

Multiple vesicles are present from birth onwards and acquire over time a typical circinate migratory pattern on an erythematous background; post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation develops gradually and may have a mottled pattern.

-

Nails may be dystrophic.

Genetics

-

Autosomal dominant inheritance.

-

Monoallelic pathogenic variants in KRT5 which affect the variable 2 domain and result in frameshift and elongated keratin 5 polypeptide cause this phenotype.

Noted Clinical Symptoms

-

Extensive skin defects on the extremities are present at birth and heal with hypo- and hyperpigmentation and skin atrophy, initially resembling burn-like scars. Skin blistering diminishes in adulthood, but fragility persists, with erosions occurring after minimal mechanical trauma.

-

Diffuse or focal plantar keratoderma.

-

Nail thickening and onychogryphosis.

-

Diffuse alopecia has been reported in some adult patients.

-

Dilated cardiomyopathy has been reported in young adulthood. Laboratory screening (pro-BNP, creatine kinase, creatine kinase MB) should be started as early as the age of 2 years, with yearly follow-ups. If pathologic values are found, cardiologic examination, ECG and cardiac ultrasound should be performed.

Genetics

-

Autosomal dominant inheritance.

-

Monoallelic pathogenic variants in the translation initiation codon of KLHL24, coding for the kelch-like member 24 cause this disorder.

-

High rate (50%) of de novo mutations.

Noted Clinical Symptoms

-

Skin blistering starts at birth and is generalized and severe in most cases. No improvement of cutaneous fragility is expected with age. Healing of lesions leads to post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation.

-

Absence of keratin 5 leads to widespread blisters and erosions and early lethality.

Genetics

-

Autosomal recessive inheritance.

-

Biallelic nonsense, missense or frameshift KRT14 pathogenic variants.

-

Biallelic loss-of-function or missense KRT5 pathogenic variants.

Noted Clinical Symptoms

-

Skin blistering starts at birth or in childhood and is mostly localized to acral extremities.

-

Plantar keratoderma.

-

Nail dystrophy.

Genetics

-

Autosomal recessive inheritance.

-

Biallelic loss-of-function pathogenic variants in DST lead to absence of BP230 and cause this subtype.

Noted Clinical Symptoms

-

Generalized skin blistering starts at birth or in infancy. Blistering tendency may diminish with age, while crusts and scabs reflect the fragility of the skin.

-

Mild mottled pigmentary changes may develop.

Genetics

-

Autosomal recessive inheritance.

-

Biallelic loss-of-function pathogenic variants in EXPH5 lead to absence of exophilin 5 and cause this subtype.

Noted Clinical Symptoms

-

Skin blistering starts at birth, is mainly acral but may be widespread. The autosomal dominant subtype is characterized by a mild course, mainly acral erosions and postlesional violaceous and hypopigmented macules. Only three cases with the autosomal recessive subtype have been published yet, all of intermediate severity.

-

Plantar keratoderma.

-

Dystrophic thickened nails, sometimes onychogryphosis.

-

No muscular dystrophy.

Genetics

-

Autosomal dominant or recessive inheritance.

-

The monoallelic PLEC pathogenic variant, c.5998C>T, p.R2000W causes the autosomal dominant subtype previously known as EBS Ogna.

-

Biallelic pathogenic variants in the exon 1a of the PLEC1a isoform (expressed in skin, but not in muscles), in particular, c.46C>T, p.R16*, cause the autosomal recessive subtype.

Noted Clinical Symptoms

-

Generalized skin blistering starts at birth and is of intermediate severity. Blistering tendency diminishes with age.

-

Focal plantar keratoderma.

-

Nail dystrophy and loss.

-

Mucosal involvement including oral, ocular and urethral mucosae is common.

-

Dental anomalies.

-

Muscular dystrophy starts at a variable age, ranging from infancy to adulthood.

-

Cardiomyopathy may be associated.

-

Granulation tissue and stenosis of the upper respiratory tract and hoarseness may occur.

-

Muscular dystrophy is usually life-limiting in childhood or early adulthood.

-

Pyloric atresia may be associated in rare cases.

Genetics

-

Autosomal recessive inheritance.

-

Biallelic loss-of-function pathogenic variants in PLEC coding for plectin cause this phenotype. They result in lack of immunoreactivity for plectin and a plane of cleavage deep within the basal pole of the basal keratinocytes.

Noted Clinical Symptoms

-

Widespread full-thickness congenital absence of skin.

-

Pyloric atresia.

-

Involvement of the oral mucosa.

-

Anemia and growth retardation.

-

Neonatal lethal course.

Genetics

-

Autosomal recessive inheritance.

-

Biallelic loss-of-function pathogenic variants in PLEC cause this phenotype.

Noted Clinical Symptoms

-

Only a few individuals with this subtype have been reported so far in the literature.

-

Skin blistering starts at birth and is widespread primarily in the pretibial area but also scattered on other parts of the body, particularly those exposed to trauma.

-

Facial freckling, poikiloderma and atrophy of the skin, and acrogeria of the backs of the hands on the sun-exposed areas reported in one case.

-

Erosions of the oral mucous membranes.

-

Nail dystrophy.

-

Early-onset alopecia.

-

Nasolacrimal duct stenosis.

-

Oesophageal webbing and strictures.

-

Nephropathy manifesting with proteinuria. The scarcity of reported cases precludes firm screening recommendations, but annual urinalysis and urea and electrolytes should probably be undertaken following diagnosis.

Genetics

-

Autosomal recessive inheritance.

-

Biallelic loss-of-function pathogenic variants in CD151, coding for the CD151 antigen cause this EBS subtype.

“When I was about two years old... a massive blister developed on my big toe. My grandmother did an internet search of those symptoms which brought her to an EB diagnosis. Shortly after, I was officially diagnosed with Epidermolysis Bullosa [Simplex].”

Carter Dvorak, EB Simplex

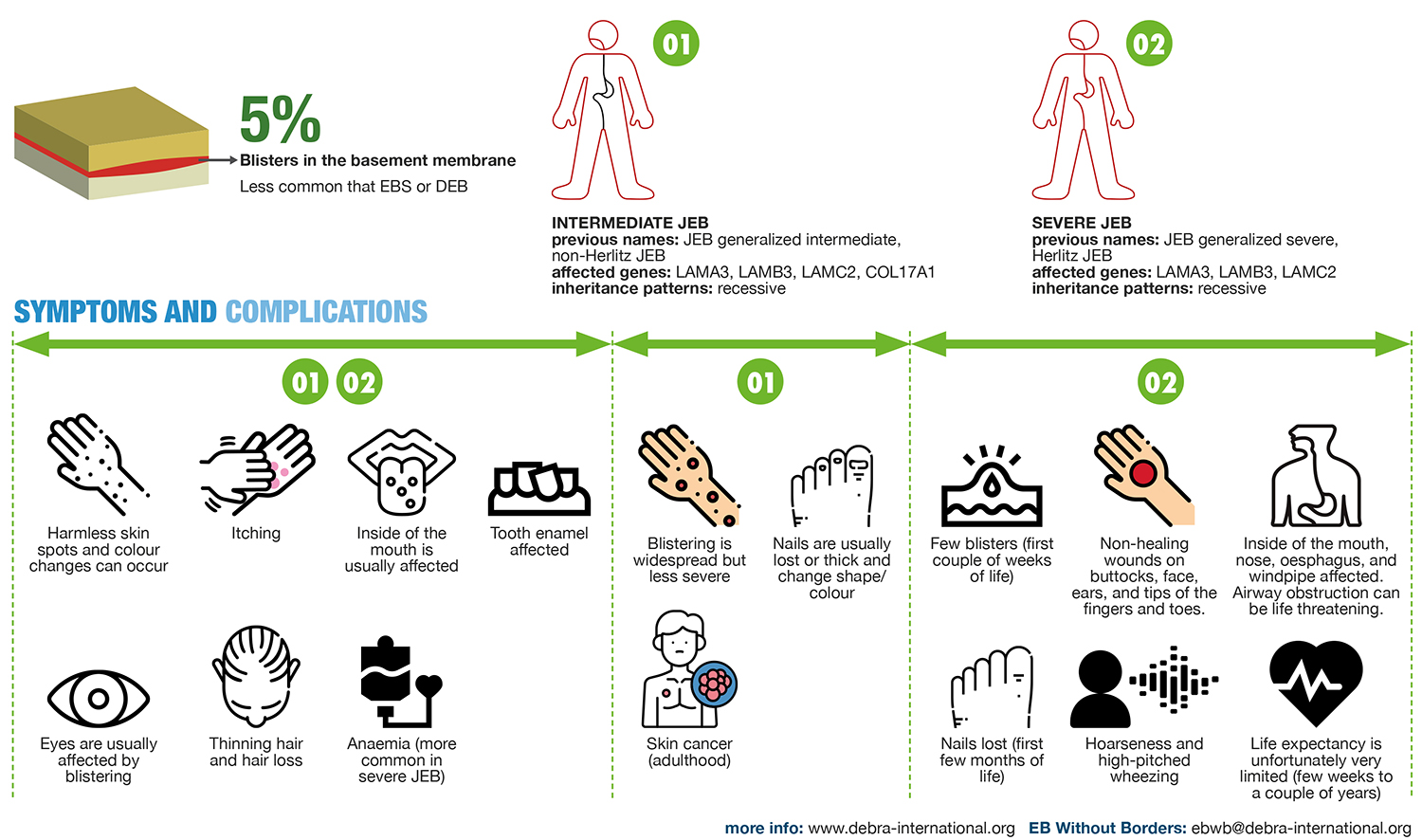

Junctional

Junctional EB is an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by skin blistering with a plane of cleavage through the lamina lucida of the cutaneous basement membrane zone (BMZ). The severity varies considerably across the two major subtypes, intermediate and severe, with the latter associated with early lethality in the first 6–24 months of life. Epidemiological data indicate that JEB is less common than simplex or dystrophic types of EB.

The two major subtypes of JEB are Severe JEB and Intermediate JEB.

Intermediate JEB

Previously known as JEB generalized intermediate, non-Herlitz JEB

Noted Clinical Symptoms

- Blistering begins at birth or shortly afterwards. Blisters tend to rupture leaving erosions, which can become extensive. Areas of ulcerated skin may be present at birth, most commonly on the lower limbs or dorsa of the feet and ankles. Blisters and ulcers may heal with atrophic scarring and variable hypo- or hyperpigmentation.

- Blistering is generalized but less severe in intermediate JEB, usually without the tendency for developing chronic granulation tissue although this can occur in chronic wounds.

- Development of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) can occur in adulthood.

- EB naevi may occur.

- Involvement of the oral mucosa occurs.

- Ocular involvement with corneal blistering and erosions. Pannus formation, scarring and symblepharon may follow episodes of blistering.

- Involvement of the genitourinary tract can occur but most commonly presents in older individuals with urethral stricture disease.

- Nails are usually lost or dystrophic with atrophy, thickening or ridging of the nail plate.

- Scarring or non-scarring alopecia and diffuse hair loss can occur.

- Dental enamel defects occur.

Severe JEB

Previously known as JEB generalized severe, Herlitz JEB

Noted Clinical Symptoms

- Blistering begins at birth or shortly afterwards. Blisters tend to rupture leaving erosions, which can become extensive. Areas of ulcerated skin may be present at birth, most commonly on the lower limbs or dorsa of the feet and ankles. Blisters and ulcers may heal with atrophic scarring and variable hypo- or hyperpigmentation.

- Usually results in death in the first 24 months due to failure to thrive, airway involvement or sepsis.

- Infants usually develop profound failure to thrive despite adequate nutritional intake.

- Blisters may be few the first couple weeks of life and tend to occur on the buttocks, elbows, and around the nails; however, despite an initially mild clinical picture, JEB severe must be suspected. From a few weeks to months of age, wounds may become chronic with a bed of friable granulation tissue. This commonly affects the face, ears and distal digits. Persistent large gluteal wounds are common.

- Involvement of the oral mucosa occurs. Typically associated with laryngeal mucosal involvement with blistering, erosions, granulation tissue and scarring giving rise to hoarseness, stridor and potentially life-threatening airway obstruction.

- Ocular involvement with corneal blistering and erosions. Pannus formation, scarring and symblepharon may follow episodes of blistering.

- Involvement of the genitourinary tract can occur.

- Loss of all nails in the first few months of life with the development of friable granulation tissue and soft tissue swelling of the distal digits.

- Scarring or non-scarring alopecia and diffuse hair loss can occur.

- Anaemia is common.

- Dental enamel defects occur.

Noted Clinical Symptoms

- Full thickness skin loss over extensive areas of the head, trunk and limbs at birth.

- Subsequent severe skin fragility.

- Skin loss can cause deformity of structures such as the ears and nose. Severe phenotypes can present with rudimentary ears.

- Nail dystrophy and loss.

- Pyloric atresia is usually evident within the first days-week of life.

- May have atresia at other gastrointestinal sites e.g. duodenal or anal.

- Usually lethal within the first few weeks of life despite surgical correction of pyloric atresia.

- Milder, non-lethal forms have less severe skin and nail involvement but with frequent genitourinary tract involvement.

Genetics

- Biallelic loss-of-function, splice site or missense pathogenic variants in ITGA6 result in a severe and rapidly lethal phenotype.

- Biallelic loss-of-function or splice site pathogenic variants in ITGB4 that result in loss of 4 integrin result in a severe and rapidly lethal phenotype.

- Biallelic loss-of-function, missense, splice site or in-frame deletion mutations in ITGB4 which result in reduced 4 integrin expression result in a milder form of JEB with pyloric atresia.

- Biallelic mutations in ITGB4 may result in JEB without pyloric atresia.

Noted Clinical Symptoms

- Limited cutaneous fragility and blistering, often only acral.

- Variable nail dystrophy and mucosal involvement.

- Variable dental enamel defects.

- Normal hair.

Genetics

- Autosomal recessive inheritance.

- Homozygous or compound heterozygous pathogenic variants in COL17A1, LAMA3, LAMB3, LAMC2, ITGB4, ITGA3.

Noted Clinical Symptoms

- Onset of blistering from birth in flexural sites.

- Atrophic scarring.

- Dental enamel abnormalities.

- Variable nail loss.

Genetics

- Pathogenic variants associated with residual expression of laminin 332.77

Noted Clinical Symptoms

- Onset of skin fragility in childhood often starting acrally.

- Progressive fragility with age.

- Healing with skin atrophy and loss of dermatoglyphs.

- Scarring leading to flexion contractures of the fingers and reduction of mouth opening may occur with age.

- Variable dental enamel and nail involvement.

Genetics

- Autosomal recessive inheritance.

- Biallelic pathogenic variants in COL17A1, specifically the missense variant c.3908G>A, p.R1303Q, cause this phenotype.

Syn. Shabbir syndrome.

Noted Clinical Symptoms

- Onset of skin fragility from birth with blistered areas leaving erosions and granulation tissue (much more than JEB severe).

- Predilection for the face and neck.

- Nail dystrophy and loss with granulation tissue of the nail beds.

- Conjunctival and eyelid granulation tissue leading to symblepharon, scarring and impaired vision.

- Laryngeal granulation tissue leading to respiratory obstruction which can be lethal.

- Profound Anaemia is a major feature due to bleeding from over granulating wounds.

Genetics

- Autosomal recessive inheritance.

- Most cases in Punjabi Muslim individuals with a homozygous founder single nucleotide insertion mutation in exon 39 of LAMA3 which is specific to the LAMA3A isoform.

- Compound heterozygosity for mutations in LAMA3A and LAMA3 result in a similar JEB-LOC phenotype.

syn. ILNEB, interstitial lung disease, nephrotic syndrome and epidermolysis bullosa

Noted Clinical Symptoms

- Variable cutaneous features with absence or presence of skin fragility from infancy.

- Nails may be dystrophic and hair may be sparse.

- Interstitial lung disease and nephrotic syndrome predominate the phenotype, and can be diagnosed soon after birth.

- Death in infancy or early childhood is the norm.

Genetics

- Most reported cases result from homozygous loss-of-function pathogenic variants in ITGA3.

- Missense ITGA3 mutations reported in milder cases surviving to later childhood.

“Mobility is the hardest thing for me and being very cautious about my activities in order to lessen the trauma...”

Winnie Bruce, Junctional EB

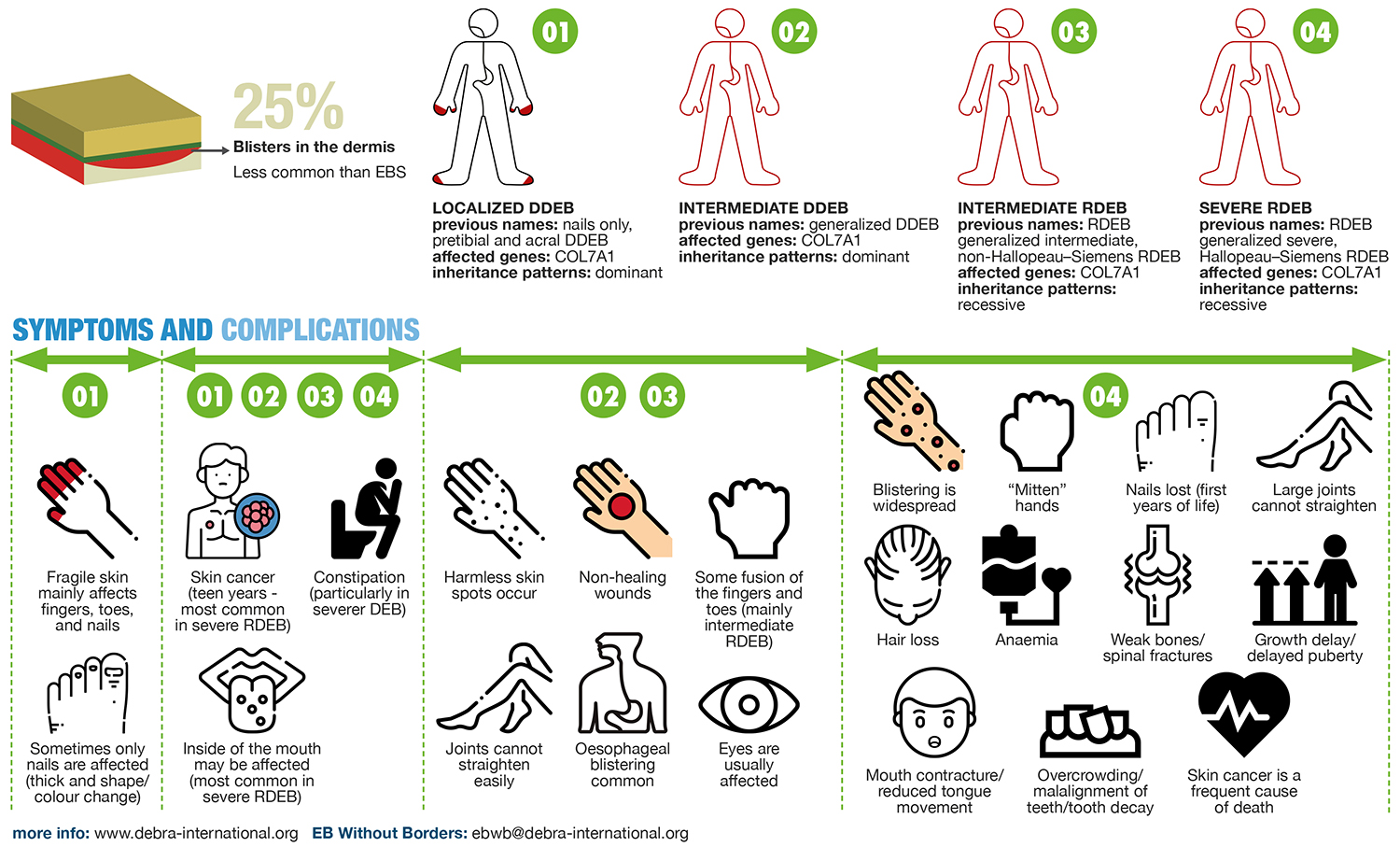

Dystrophic

Dystrophic EB is characterized by a plane of skin cleavage just beneath the lamina densa in the most superficial portion of the dermis. Ultrastructurally, this corresponds to the level of the anchoring fibrils, reflecting the underlying molecular pathology in the gene coding for the main component of these structures, type VII collagen. DEB may be inherited as a dominant or recessive trait; generally, RDEB is more severe than dominant disease (DDEB); however, there is considerable phenotypic overlap between types.

Major subtypes of DEB include Localized DDEB, Intermediate DDEB, Intermediate RDEB, and Severe RDEB.

Localized DDEB

Previously encompassing nails only, pretibial and acral DDEB

Noted Clinical Symptoms

- Onset of skin fragility is usually from birth or early childhood and is limited in anatomical extent. This may be predominantly acral in distribution or just affect the nails with progressive dystrophy and loss, mainly of the toenails. Some individuals have a predominantly pretibial distribution of blistering and scarring; in this form symptoms may not develop until later childhood or adulthood.

- May present solely with loss or dystrophy of the nails, most commonly the toenails.

- EB naevi may occur.

- The oral mucosa may be involved with blistering, erosions and scarring.

- Recurrent blistering and fissuring around the anal margin are common in all forms of DEB.

- Constipation is common due to pain on defection resulting from anal fissuring and blistering, exacerbated by poor intake of fibre-rich foods when intake is compromised.

Intermediate DDEB

Previously known as generalized DDEB

Noted Clinical Symptoms

- Manifest with more generalized skin fragility, scarring and milia from birth or early childhood, with a predilection for bony prominences including the elbows, knees, ankles and dorsa of the hands and feet.

- The risk of developing SCC is also increased in intermediate DDEB, RDEB and, to a lesser extent, localized DDEB, but is less common than in severe RDEB and occurs later in adulthood.

- EB naevi may occur.

- The oral mucosa may be involved with blistering, erosions and scarring.

- Oesophageal blistering and scarring are common in severe and intermediate forms of DEB. Left untreated, progressive strictures can significantly limit oral nutritional intake.

- Recurrent blistering and fissuring around the anal margin are common in all forms of DEB.

- Involvement of the conjunctiva and cornea is common, leading to corneal erosions, scarring, pannus, symblepharon formation and reduced visual acuity.

- Nail dystrophy and loss secondary to trauma are common.

- Nutritional impairment may occur; it results from reduced intake due to factors such as microstomia, dental caries and oesophageal stricture disease, in combination with increased metabolic demands due to chronic wounds, infection and inflammation.

- Constipation is common due to pain on defection resulting from anal fissuring and blistering, exacerbated by poor intake of fibre-rich foods when intake is compromised.

Intermediate RDEB

Previously known as RDEB generalized intermediate, non-Hallopeau-Siemens RDEB.

Noted Clinical Symptoms

- Manifest with more generalized skin fragility, scarring and milia from birth or early childhood, with a predilection for bony prominences including the elbows, knees, ankles and dorsa of the hands and feet.

- Mild flexion contractures or a striate-pattern of keratoderma of the fingers and limited digital fusion in the proximal digital web spaces may occur.

- The risk of developing SCC is also increased in intermediate DDEB, RDEB and, to a lesser extent, localized DDEB, but is less common than in severe RDEB and occurs later in adulthood.

- EB naevi may occur.

- The oral mucosa may be involved with blistering, erosions and scarring.

- Oesophageal blistering and scarring are common in severe and intermediate forms of DEB. Left untreated, progressive strictures can significantly limit oral nutritional intake.

- Recurrent blistering and fissuring around the anal margin are common in all forms of DEB.

- Involvement of the conjunctiva and cornea is common, leading to corneal erosions, scarring, pannus, symblepharon formation and reduced visual acuity.

- Nail dystrophy and loss secondary to trauma are common.

- Nutritional impairment may occur; it results from reduced intake due to factors such as microstomia, dental caries and oesophageal stricture disease, in combination with increased metabolic demands due to chronic wounds, infection and inflammation.

- Constipation is common due to pain on defection resulting from anal fissuring and blistering, exacerbated by poor intake of fibre-rich foods when intake is compromised.

Severe RDEB

Previously RDEB generalized severe, Hallopeau-Siemens RDEB

Noted Clinical Symptoms

- Skin blistering is widespread and manifests from birth with significant fragility from minor skin trauma. From infancy, blistering is more marked over bony prominences and causes extensive scarring which can lead to flexion contractures of the large joints.

- Progressive pseudosyndactyly (digital fusion), flexion contractures and distal resorption of the digits lead to mitten deformities of the hands and feet.

- Chronic wounds are frequent at sites of repeated blistering.

- Congenital skin ulceration is a common presenting feature in neonates.

- The development of aggressive cutaneous SCC is very common and a frequent cause of death, increasing in incidence from the teen years onwards, arising in areas of repeated trauma, wounds and scarring.

- EB naevi may occur.

- The oral mucosa may be involved in all forms of DEB with blistering, erosions and scarring but changes are most extensive and marked in severe RDEB.

- Progressive scarring leads to microstomia and ankyloglossia, which can result in dental overcrowding and malalignment, and the development of secondary caries.

- Oesophageal blistering and scarring are common in severe and intermediate forms of DEB. Left untreated, progressive strictures can significantly limit oral nutritional intake.

- Recurrent blistering and fissuring around the anal margin are common in all forms of DEB.

- Involvement of the conjunctiva and cornea is common, leading to corneal erosions, scarring, pannus, symblepharon formation and reduced visual acuity.

- Urethral strictures may occur.

- Nail dystrophy and loss secondary to trauma are common. Nails are usually lost progressively during the first several years of life.

- Scarring alopecia and crusting are common with increasing age.

- Nutritional impairment is common; it results from reduced intake due to factors such as microstomia, dental caries and oesophageal stricture disease, in combination with increased metabolic demands due to chronic wounds, infection and inflammation.

- Constipation is common due to pain on defection resulting from anal fissuring and blistering, exacerbated by poor intake of fibre-rich foods when intake is compromised.

- A mixed picture of Anaemia due to iron deficiency and inflammation is common.

- Osteopenia, osteoporosis and vertebral fractures are common and may be due to reduced mobility, chronic inflammation, vitamin D and calcium deficiency, and pubertal delay.

- Renal impairment and failure may occur as a result of acute kidney injury, post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis, renal amyloid or IgA nephropathy.

- Cardiomyopathy may rarely arise.

Noted Clinical Symptoms

- Usually presents initially as localized or intermediate DDEB or RDEB in childhood and early adulthood.

- Characterized by intensely pruritic, excoriated violaceous papules or linear plaques and scars particularly on the lower legs, thighs and arms which can become more progressive from adolescence through adulthood.

- Nail dystrophy and milia are common.

- May co-exist with non-pruriginosa DEB within families.

Genetics

- Autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive inheritance.

- Monoallelic or biallelic mutations in COL7A1 similar to those identified in non-pruriginosa DDEB or RDEB without identification of a specific genotype-phenotype correlation for the pruriginosa phenotype.102–104

syn. bullous dermolysis of the newborn

Noted Clinical Symptoms

- Skin blistering presents at or shortly after birth, usually on the extremities.

- Aplasia cutis of the lower limbs may be present.

- Scarring and milia occur at sites of blistering.

- Skin fragility improves spontaneously and may resolve completely over the first year or two of life although nail dystrophy, particularly of the toenails, may persist throughout life.

Genetics

- Autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive.

- COL7A1 missense mutations, especially glycine substitutions, are most commonly associated but in-frame deletion, premature termination codon and alternative splicing mutations also described.

- Characteristic intra-epidermal retention of type VII collagen on immunohistochemistry and stellate bodies in dilated rough endoplasmic reticulum on transmission electron microscopy. These changes tend to improve in parallel with phenotypic improvement.

Noted Clinical Symptoms

- In the neonatal period and childhood skin blistering is usually generalized and of intermediate severity.

- From adolescence to early adulthood, a predilection for flexural sites develops, specifically in the axillae, groins, perianal area and natal cleft. In women, there may be marked vulvovaginal and inframammary skin blistering.

- Mucosal disease with blistering and scarring in the mouth and oesophagus is characteristic.

- Involvement of the external auditory canal may lead to narrowing or complete occlusion.

- Nail involvement is common.

Genetics

- Autosomal recessive inheritance.

- Usually results from compound heterozygosity for a loss-of-function COL7A1 mutation in combination with a missense mutation; specific glycine and arginine substitutions have been suggested as causative for this specific phenotype.

Noted Clinical Symptoms

- Skin fragility usually presents at or shortly after birth but may rarely be of late onset in adulthood.

- Blistering is limited in extent; it may affect predominantly the hands and feet, but in others may be restricted to the pretibial area.

- Nail dystrophy and loss are common.

- Oral and esophageal mucosal involvement are usually mild or absent.

Genetics

- Autosomal recessive inheritance.

- Compound heterozygosity for COL7A1 missense, splice site and frameshift mutations described.

Noted Clinical Symptoms

- Severe skin and mucosal fragility presenting from birth indistinguishable from severe RDEB.

- May have a family history of DDEB in family members.

Genetics

- Compound heterozygosity for a dominant COL7A1 glycine substitution mutation and a recessive mutation on the second allele.

“It presented shortly after birth with blisters all over my body. In 1971, they did not know what it was and of course, thought I was contagious, so they had me in an incubator for a couple of weeks.”

Jan Marhefka, Recessive Dystrophic EB

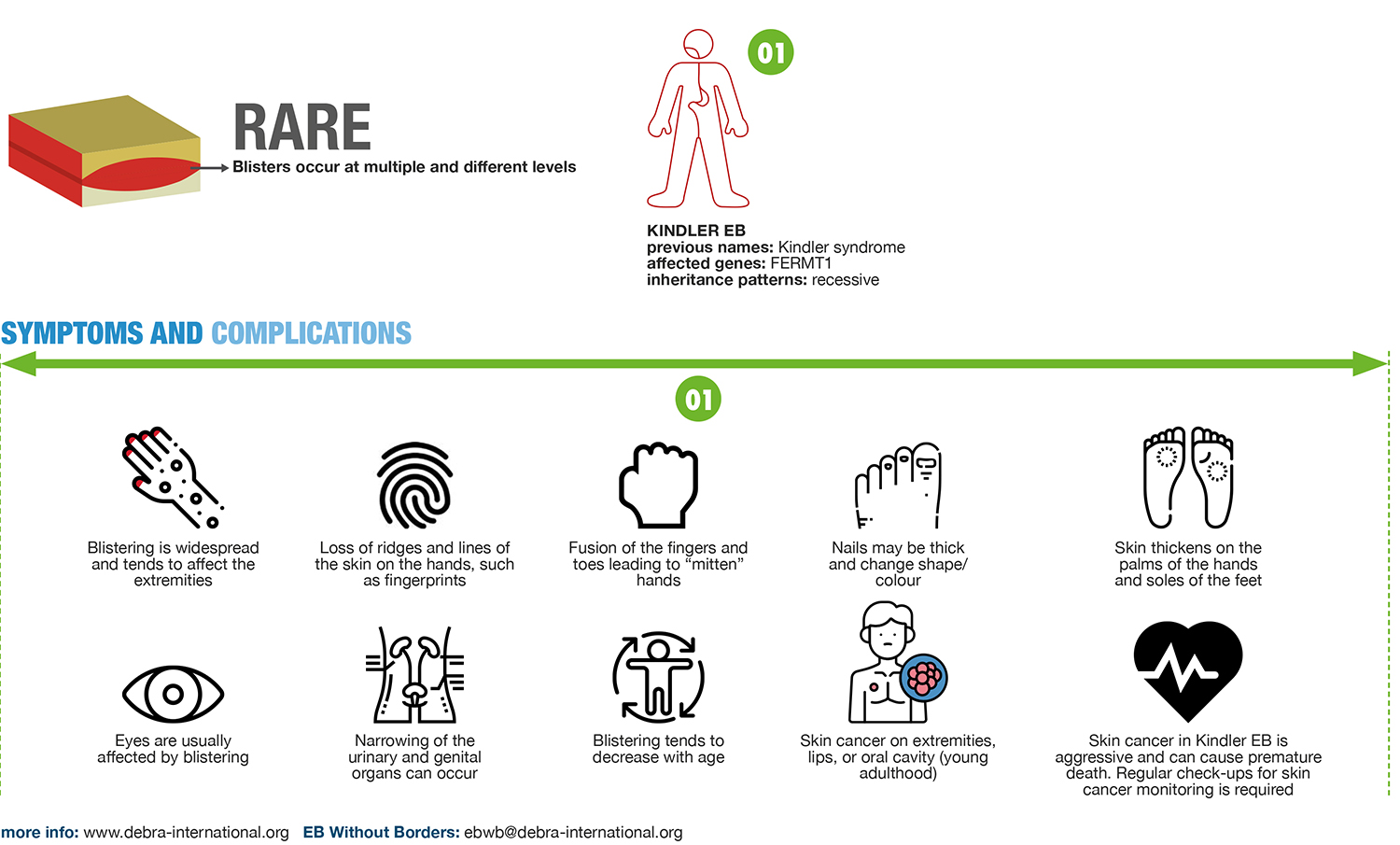

Kindler

Kindler EB is a rare type of EB with about 250 affected individuals reported worldwide since the first description in 1954. It is more common in isolated or consanguineous populations.

Noted Clinical Symptoms

- Skin blistering begins at birth and is generalized with predilection for the extremities. The tendency to blistering decreases with age.

- Skin atrophy and poikiloderma start on the dorsal aspects of the hands and on the neck during childhood and extend to the entire integument.

- Diffuse palmoplantar keratoderma and loss of dermatoglyphs.

- Photosensitivity is of variable severity.

- SCC on extremities, lips or oral cavity develop in young adulthood, have a severe course and cause premature death related to the disease.

- Gingivitis with tooth loss, gingival hyperplasia, oesophageal strictures and colitis in a few cases.

- Urogenital strictures.

- Ectropion, corneal erosions.

- Nail dystrophy.

Credit: C. Has et al, “Consensus reclassification of inherited epidermolysis bullosa and other disorders with skin fragility”, British Journal of Dermatology, October 2020

Infographics Credit: DEBRA International, “What Is EB?” Infographics

Page updated March 2021.